Two B-52s power over the Pacific Ocean on Aug. 2 as part of US Indo-Pacific Command’s Continuous Bomber Presence in the region. Photo: A1C Gerald Willis

The last B-52 rolled off the production line in 1962. If Air Force plans hold up, the B-52 will be approaching nearly a century of service by 2050. To keep the airplane flying, the service plans to equip each B-52 with new engines, which are expected to be so much more maintainer-friendly and efficient that they’ll pay for themselves in just 10 years.

The Air Force is also looking at the B-52 re-engining as a pathfinder program to explore ways to speed up contracting. Instead of an elaborate, paper-intensive comparison of candidate engines—in which the government makes educated guesses about capability—the service plans to conduct a “digital fly-off” between power plants, using computer simulations. This virtual fly-off will compare engines for fuel efficiency, maintenance requirements, and performance under a wide variety of conditions.

“I think we’re going to learn a lot from this program,” Air Force acquisition chief William Roper said in September. “Digital engineering is a much better way to assess [options] than a paper input with a lot of government expertise trying to fill in the gaps. Let’s just simulate the system and pick.”

Roper said streamlined contracting and the digital fly-off will cut 3.5 years from the original 10-year time line between setting requirements and the decision to proceed to production.

“I’m much more likely to believe” the data derived from a digital comparison than what could be gleaned from a “paper … analog” evaluation,” he said.

In October, USAF decided an upgrade of the existing Pratt & Whitney TF-33 power plants—original equipment when the B-52Hs were manufactured in 1962—is off the table.

“Refurbs are no longer being considered,” a Global Strike Command spokesman told Air Force Magazine. As recently as September, Pratt & Whitney was pushing to refurbish the existing B-52 engines, adding new technology to increase their efficiency and reduce maintenance, as a lower-cost alternative to buying new.

However, “the Air Force has decided that the existing engines are not viable” for a service life that will take the B-52Hs into their 90th year of service, AFGSC chief of B-52 requirements Maj. Gerald Isabelle, said in an interview.

The re-engining plan is funded at $1.5 billion through the five-year Future Years Defense Program, Isabelle noted, but an overall cost has not been publicly released. A former AFGSC commander, Gen. Robin Rand, told this publication in March 2017 that initial estimates pegged B-52 re-engining as costing about $7 billion.

Airmen faix the cover on a BUFF’s J57 jet engine at Offutt AFB, Neb., in the late 1950s. The Pratt & Whitney power plant was the first engine installed on the venerable bomber, only to be replaced by the quieter TF-33 in 1961. Photo: USAF/AFA Library

USAF’s “Bomber Vector” plan, which rolled out in early 2018, estimated the cost of B-52 service life extension—including the re-engining other capability improvements—at $22 billion, less savings resulting from the re-engining work. The report forecast the savings at $10 billion, saying the equipment “pays for itself in fuel, depot and maintenance costs, and maintenance manpower in the 2040s,” according to the document.

Officially, the project is called the B-52 Commercial Engine Replacement Program (CERP), and the Air Force has already hosted a number of industry days to dicuss it at Barksdale AFB, La., most recently in mid-November. The stated goal: Obtain a “commercial, off-the-shelf, in-production engine,” according to a FedBizOpps (Federal Business Opportunities) announcement regarding the industry day.

The Air Force wants to buy a replacement for each of the eight TF-33s on all of its 76 B-52s, or around 608 engines in all (plus some attrition spares in case of accidental damage). Similar to the existing engines, they’ll be housed in twin-engine pods.

Isabelle said the Air Force is looking for 25 to 30 percent better fuel efficiency and as much as 40 percent improvement in range. USAF has also expressed a desire for a cleaner-burning power plant, producing less greenhouse gases than the existing engines.

Increasing fuel efficiency by 25 to 30 percent is “huge,” Roper said, paying off not only in cost savings, but also in range or time on station.

Computer models will help evaluate the trade-offs between cost and capability as the competition runs its course, Roper said. “If one vendor can provide 30 percent fuel efficiency, but their engine is more expensive, and another has less [efficiency], but their engine is cheaper, that’s an interesting trade,” he explained. “It’s not clear what the right answer is.”

The Air Force considered re-engining the B-52 in 2007, when it looked at using the aircraft for theater-wide electronic warfare. The B-52 Standoff Jammer, or SOJ, concept would have kept the bombers on station after releasing standoff weapons to provide wide-area jamming in the battlespace, leaving jamming escort duties to the Navy EA-6 and EA-18. New engines were needed to increase the bombers’ range and to power the jamming equipment.

But the SOJ concept was never put into effect.

In late 2014, having learned how commercial airlines were saving on maintenance and fuel costs with modern engines, then-Lt. Gen. Stephen “Seve” Wilson resumed the push as head of Global Strike Command. Now USAF Vice Chief of Staff, Wilson and his successor at AFGSC, Gen. Robin Rand, floated the idea of leasing the engines as an alternative way to fund the project.

The Air Force has also considered replacing the B-52’s eight engines with four large turbofans, as is typical on commercial airliners. Engineering challenges made that approach nonviable. Potential interference with flaps and control surfaces, ground clearance issues, yaw effects, the need for extensive new flight testing and weapon separation evaluations, the need to replace large sections of the cockpit and throttles, and to redesign the rudder ruled out such a change. USAF has opted to stick with eight engines of the class that typically powers large business jets.

Modern engines are so much more reliable than the TF-33s that were once installed, the new engines will probably never have to be removed. The meantime between overhauls for that class of engines is typically around 30,000 hours—greater than the number of hours the service plans to fly the bombers for the rest of their service lives.

SrA. Austin McCullough inspects a B-52 engine at Barksdale AFB, La., in January 2018. USAF declared an upgrade or refurbishment of the engine type was off the table. Photo: A1C Sydney Campbell

The B-1 and B-2, which are at least 22 and 30 years younger, respectively, will retire before the B-52 for a range of reasons, according to the Bomber Vector study:

- The B-52 has in recent years racked up mission capability rates of 60 percent, far above that of the B-1 and B-2, which are at about 40 and 35 percent, respectively.

- The B-52 costs about $70,000 per flying hour, roughly half that of the B-2—even before it gets more efficient engines.

- The B-52 “has good bones,” Rand said, noting that the B-52H spent most of its service life on ground alert for nuclear operations, and still has many thousands of hours of airframe life remaining.

Not all of the modernization plans for the B-52 are funded so far. “We are working through our leadership to develop a strategy on how to approach the acquisition,” James Hunsicker, AFGSC’s deputy chief of bomber requirements, told Air Force Magazine in an interview. “We are working to get those approved by the [AFGSC] commander and, ultimately, by Dr. Roper, who has been interested in how we’re going to attack that problem.”

Asked if the B-52 can make it to 2050, Hunsicker said, it “would surprise you at how sound” the aircraft’s sheet metal and structural components remain after five decades. However, “modernization [means] keeping up with the environment it will fly in,” he added. “There are things that will always have to be dealt with because they will age out, and radar and engines are two of the main areas you always want to keep current and capable.”

Planning for a radar replacement is well along, Hunsicker said, and “defensive systems will have to be kept as capable as possible.” There will also need to be frequent avionics refreshes.

“We will continue to monitor … what needs to be updated,” he asserted.

“That’s true of all airplanes, and the B-52 is no different.”

Indeed, B-52 updates have been underway for some time. Installation of Link 16 is being accomplished, and the CONECT “digital backbone”—one of the most extensive capability improvements in decades—is being finished. New VLF and AEHF radios are being installed, the 1760 Internal Weapons Upgrade Bay is complete, and “another increment to follow” has been mapped out, Hunsicker explained.

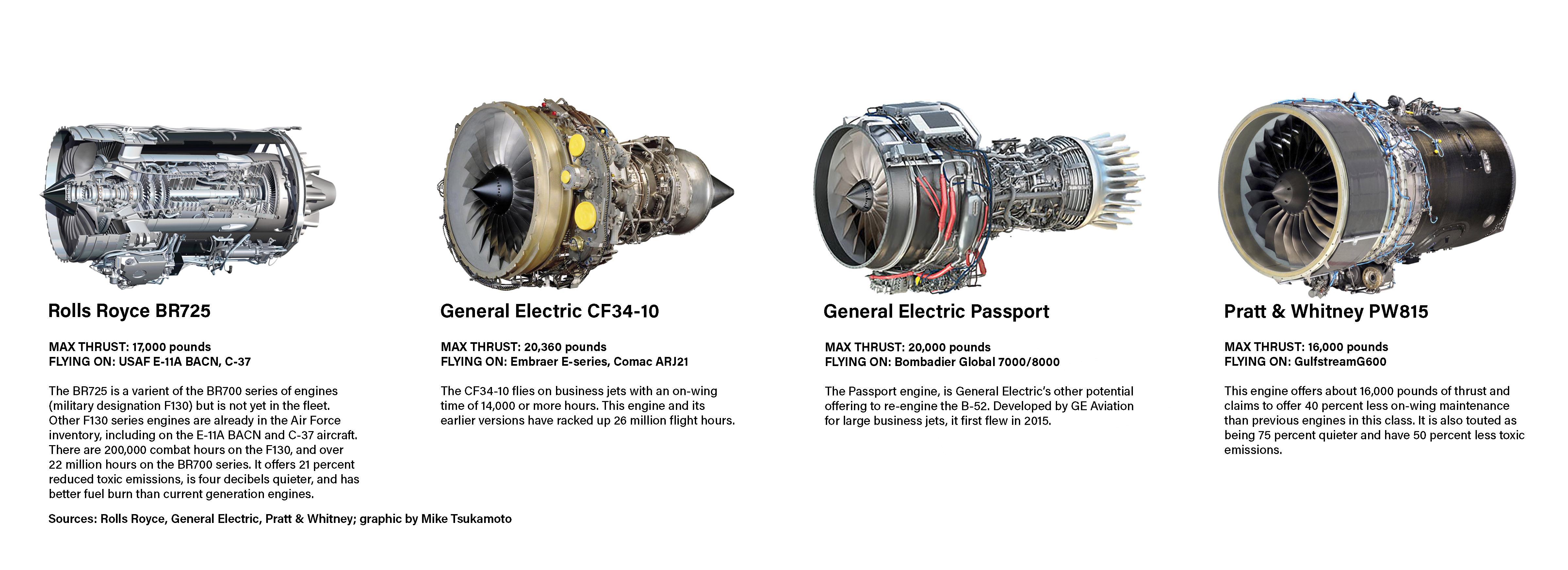

Sources: Rolls-Royce, Pratt & Whitney, and General Electric. Graphic by Mike Tsukamoto

CHOOSING AN ENGINE

Boeing, the original manufacturer and a chief supporter of the B-52, will be the integrator on the re-engining effort, but the Air Force will choose the engine and supplier, Boeing will advise the Air Force on the impact each potential engine would have on the B-52’s flight profile and weapons carriage.

A Pratt & Whitney spokesman said that if the Air Force opts not to refurbish the TF-33, “the best solution” would be a modified PW815, the engine Pratt supplies for Gulfstream’s G600 business jet.

“We know this aircraft’s engine and power requirements like no one else,” a Pratt spokesman told Air Force Magazine. “We are confident that the options we offer will address propulsion, fuel burn, and power generation (including APU) requirements for the B-52 to 2030 and beyond.”

GE Aviation has two offerings that could play in the B-52 derby: The CF34-10 and the new “Passport” engine. Karl Sheldon, a manager in GE’s aviation manufacturing division, said the final requirements will determine the best choice between the two.

“The CF34 offers proven reliability,” he said, having racked up 26 million flight hours, while the new Passport offers unprecedented “fuel burn, range, or time on station.” The company will settle on an offering as soon as it’s clear which one will best match USAF’s stated requirements.

Rolls-Royce jumped into the re-engining contest before it was even announced, touting its BR725 power plant—military designation F130—as the ideal candidate as early as September 2017. Company officials said their offering would cut carbon emissions by 95 percent while handily meeting USAF’s notional-range and fuel-efficiency requirements.

The F130 powers the RQ-4 Global Hawk, the E-11 BACN, and the new Compass Call aircraft, which is a special-mission version of the Gulfstream 650, so it’s already in the Air Force inventory.

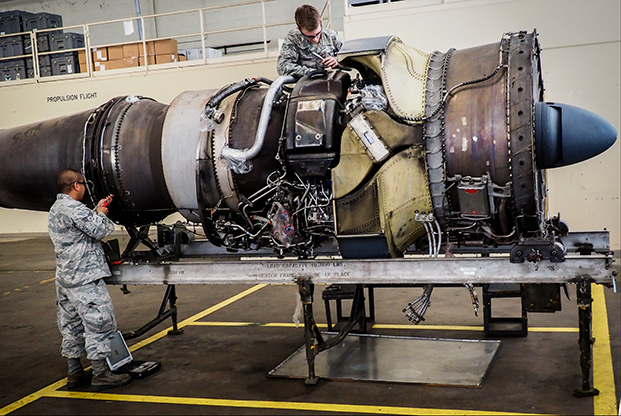

SrA. Jovie Abaya and SrA. Bradley Hardee work on a B-52 engine trainer at Barksdale. The hardy engine is considered “not viable” for a service life that will take the B-52 into their 90th year of service. Photo: SrA. Nizer Da Cunha

Despite rumors to the contrary, Isabelle said the Air Force is not looking for substantially better physical performance from the new engines—for example, in time to climb or top speed—although that may turn out to be a welcome by-product.

Lt. Gen. Arnold W. Bunch Jr., (then-USAF’s top uniformed acquisition official, nominated to head AFMC at press time), said the competition will look across a wide range of cost considerations.

The question is not just “how often do I have to take it off the wing?” Bunch said. More significantly, it is also “do I still have to have the depot?”

The TF-33 depot is at Tinker AFB, Okla., and costs to maintain the engine have risen sharply in the past 11 years. Operationally, Bunch said—and this will be a factor in the ultimate choice—“How far back from the war can the aircraft be and still be effective in an A2AD [anti-access/area denial] environment? All of those are things that weigh into how we look at this.”

Hunsicker predicted that within six months—after revelations in the Fiscal 2020 budget—the Air Force will have a solid plan about what will need to be done to the B-52 to keep it a credible, safe, and capable bomber for its newly extended service years.