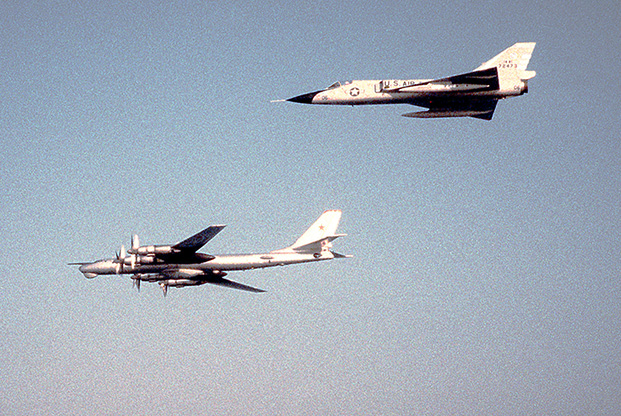

An F-4 pilot takes a self-portrait with a Tu-95 Bear bomber over the North Atlantic in 1980. Photo: MSgt. Richard Diaz

The Bear intercept is among the most enduring images of the Cold War. The ritual was played out thousands of times between 1961 and 1991 as US and Canadian air defense fighters scrambled to engage long-range Soviet bombers and reconnaissance aircraft on the periphery of North American airspace.

In the beginning, the fighters were usually USAF F-102s or F-106s. Later they were F-4s and F-15s. Sometimes the aircraft they intercepted was a Tu-16 Badger, or on occasion an M-4 Bison. By far, however, the intruder intercepted with the greatest frequency was the Tu-95 Bear. (Bear, Badger, Bison, etc., are all code names used by NATO.)

In a typical encounter, the interceptors would pull close alongside and fly formation until the Soviets left the air defense buffer zone. Both sides took pictures.

In no other Cold War setting did US and Soviet combat forces come regularly into such potentially lethal proximity. They were careful to avoid provocative actions.

Most—but not all—of the challenges were in the far north, over the Bering Sea around Alaska or in the “GIUK gap,” the open areas between land masses of Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom. Navy pilots intercepted Soviet intelligence-gathering aircraft that overflew US carriers at sea, and Air Defense Command squadrons made intercepts as far south as Florida.

_Read this story in our print issue:

In response to the increasing threat from Soviet bombers across the polar routes, the United States and Canada in 1958 formed the North American Air Defense Command, with the mission of defending the continental United States, Canada, and Alaska against air attack.

Separately, the Iceland Defense Force was organized under the auspices of NATO. It included USAF interceptors to respond to incursions of the Iceland Air Defense Interception Zone.

The first recorded intercept was Dec. 5, 1961. Two F-102s from the Alaskan Air Command’s forward operating base at Galena intercepted two Soviet bombers—Tu-16 Badgers rather than Bears—off the northwest coast in the Bering Sea.The records are fuzzy about how many intercepts took place, but it is reasonably clear that they numbered in the thousands. Intercepts following the first one in 1961 continued regularly to the end of the Cold War, then stopped for a while.

On orders from Russian President Vladimir Putin, the challenges resumed in August 2007 and continue today. The aircraft intercepted by US fighters is still the Tu-95 Bear, which has been in operation for more than 60 years in various models and configurations.

In the 1980s, an F-106 from the Massachusetts Air National Guard intercepts a Tu-95 Bear bomber off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada. Photo: USAF

OVER THE TOP

In 1946, the Army Air Forces stated a “polar concept,” which put air defense priority on the “polar approaches, namely the North Atlantic and Alaska.” In 1949, the Joint Chiefs of Staff declared that all nations capable of waging war on the United States lay north of the 45th parallel—defining, in effect, the Soviet Union as the threat—and that the shortest attack route was across the polar region.

These facts of geography took on strategic significance as the Soviets fielded bombers with enough range to reach the continental United States, beginning with the M-4 Bison in 1955 and the Tu-16 Badger in 1954. The best of them was the Tu-95 Bear, introduced in 1956. It had an unrefueled combat radius of more than 5,000 miles and long-endurance turboprop engines that gave it a top speed of 575 mph.

US air defense expanded rapidly in response. The Air Force developed the “Century series” of fighter-interceptors. The F-102 in 1956 was a stopgap solution until the superb F-106 became operational in 1959. Work began in 1957 on the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line of radars that eventually stretched from Alaska to Greenland. With the computerized Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) system, air defense commanders could direct hundreds of interceptors against hundreds of targets from huge command- and-control centers.

Sovereign US airspace extends only 14 miles from the coastline, but it was obviously imprudent to allow intruders to get that close before they were challenged. Thus “air defense identification zones” were established, reaching out into international airspace for more than 200 miles. Within those zones, aircraft would be identified, tracked, and monitored—and if need be, intercepted and escorted.

Instances of visual contact between US and Soviet aircraft date back to the early 1950s, but the serious incursions began in 1958 when radar detected Soviet bombers flying in the vicinity off the coast of Alaska. F-102 interceptors were scrambled but could not catch the intruders. Sixteen similar incidents occurred before Alaskan Air Command’s first successful intercept in 1961.

However, by the time of that intercept, the air defense buildup had peaked. The bomber threat was seen as disappearing or insignificant in the context of the more dangerous ICBM threat, which had emerged in the late 1950s.

The National Security Council in 1960 predicted “a gradual transition from a largely bomber threat to one mainly composed of ICBMs.” The CIA reported in 1961 that production of Bisons and Bears had probably ended and that the Soviets were unlikely to develop any new bombers.

A follow-on USAF interceptor, the F-108, was canceled. (See “F-108 Rapier,” September 2014, p. 114.) In the 1960s, more than half of the interceptor squadrons were deactivated. Active Duty units were concentrated around the edge of the Arctic Circle while the Air National Guard, flying F-102s and F-101s rather than the more capable F-106, took over much of the Air Defense Command alert duty in the lower 48 states.

US planners had no inkling that the bomber incursions were not nearly over or that the Tu-95 Bear would still be going strong six decades later.

An F-22 Raptor intercepts a Russian Tu-95MS bomber in November 2007. This was the first intercept for a Raptor. Photo: USAF

ALASKA AND ICELAND

Intercept activity was mainly in the polar region, where distances between the Western and Eastern hemispheres are compressed. At the Bering Strait, the US and the USSR were separated by only 50 miles. Alaska was directly across the Bering Sea from forward “jump” airfields in the Soviet Far East. For bombers at Murmansk on the Barents Sea, it was almost a straight shot along the rim of the Arctic Circle to Iceland.

The organization for air defense, which had evolved in pieces over time, was awkward. Alaskan Air Command was not part of Air Defense Command. It reported instead to US Alaskan Command. However, the commander of the unified Alaskan Command was also commander of the Alaskan NORAD region, so it worked out.

Almost 90 percent of the intercepts from Alaska were accomplished by fighters deployed to the Galena and King Salmon forward operating bases. According to the official tally, Alaska units flew 306 successful intercept missions and intercepted a total of 473 Soviet aircraft between December 1961 and the end of the Cold War in 1991.

In 1963, two Soviet aircraft eluded F-102s from King Salmon and penetrated 30 miles into American airspace over southwestern Alaska. In the ensuing furor, Air Defense Command sent F-106s on a temporary basis, but Alaska soon got F-106s of its own to replace the F-102s. Later upgrades were to the F-4E in 1970 and the F-15 in 1982.

In 1974, two Alaskan F-4s intercepted an An-24 Coke transport in distress in severe headwinds and fog and without enough fuel to get home. The Soviets landed on St. Lawrence Island and were sent safely on their way after a C-130 from Elmendorf delivered them fuel.

Alaska was not the busiest air defense sector. The majority of Cold War intercepts by far—about 3,000 of them between 1962 and 1991—were mostly around Iceland, and most were Tu-95 Bears flying out of Murmansk and from the Kola Peninsula.

Iceland had no armed forces of its own except for a coast guard. The Iceland Defense Force was a subordinate unified command of US European Command. The interceptor component of Air Forces Iceland was the USAF 57th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron at Keflavik, which intercepted more Soviet aircraft than any other unit. The squadron began with F-89 fighters in 1954, then transitioned to F-102s in 1962, F-4s in 1973, and F-15s in 1985.

The Canadians initially operated the CF-100 “Canuck” as their primary interceptor. Its cruising speed was slightly less than that of the Bear, so the Canadians replaced it with the CF-101 Voodoo. They upgraded again in 1984 to the CF-18 Hornet.

A DEW Line station near Point Lay, Alaska, in 1987. The line of radar stations ran more than 3,000 miles. Photo: TSgt. Donald Wetterman

THE MIGHTY BEAR

The Tu-95 was the Tupolev Design Bureau’s masterpiece. To achieve the range desired, it used powerful turboprop engines instead of fuel-guzzling turbojets. Each of the eight engines drove contrarotating propellers—two of them on each shaft, turning in opposite directions.

The result was a big airplane with more than enough range for a round-trip mission to the continental United States. It was only a little slower than a turbojet.

The Bear was notoriously noisy. The blade tips of the large-diameter propellers, churning supersonically, made so much racket that the listening devices on submerged submarines could hear the Tu-95 flying overhead. The Bear also reflected a large image on the radar return so its approach was seldom a surprise, especially when the E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) deployed to Alaska and Iceland in the 1980s to aid in detection and tracking.

The Tu-95 remained the mainstay of Soviet strategic aviation, even after introduction of the much faster Tu-22 Backfire and the Mach 2 Tu-160 Blackjack. The Soviets reopened the Tu-95 production line in 1981 and brought out a series of new models and variations.

Notable among these was a maritime patrol aircraft for the Soviet navy, designated the Tu-142 although it was still called the Bear. The latest air force variant is the Tu-95MS Bear H, which carries up to 10 cruise missiles.

CAT AND MOUSE

Tu-95 incursions were not actual attempts to break through the defenses to attack the United States or Canada. They were cat-and-mouse-style intelligence operations of a kind that both sides had conducted since the 1950s.

The US and the USSR routinely flew on the edges of each other’s territory to collect electronic intelligence, helping to crack codes, discover command and control procedures and preparations, and gather all sorts of valuable information. It also enabled them to test and time the response of the interceptors and determine the accuracy of the radars. They did not get maximum value from the mission unless the defenses were activated, so they had to go close enough to induce the fighters to scramble.

US overflights of the USSR ended in disaster in 1960 when the Soviets brought down a U-2 over Sverdlovsk and captured the CIA pilot. After that, the United States conducted its reconnaissance missions on the periphery, using RB-47 “ferret” aircraft at first and later the RC-135.

When in 1983 the Soviets shot down Korean Airlines Flight 007—which had wandered far off course and twice overflew Soviet territory—they thought it was an American RC-135, which had been working in the vicinity a few hours previously.

Bear incursions and intercepts continued with increasing frequency through the 1980s. In 1985-1986 alone, the interceptor squadron at Keflavik conducted 340 intercepts. Typically, the Soviet aircraft were Tu-95s from Murmansk, discovered and reported by Norwegian radar as they passed the North Cape, then picked up and tracked by the defenses in Iceland.

As the Cold War came to an en, US President George H. W. Bush and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev mutually called a halt to the strategic confrontation. The era of Bear intercepts was presumed to be history.

There were scattered incidents. F-15s intercepted two Tu-95s off the shore of Iceland in 1999 but US spokesmen dismissed “two propeller bombers” as not being “a particularly big deal.”

Air defenses, allowed to deteriorate, were reinvigorated after hijacked airliners crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001 but the focus was on terrorists, not the Russians.

THE PUTIN ROUND

In what was interpreted as a show of force, Putin announced Aug. 17, 2007, that Russian bombers would resume the long-distance patrol flights. “Starting today, such tours will be conducted regularly and on the strategic scale,” Putin said. “Our pilots have been grounded for too long.”

The same day, Tu-95 Bears and Tu-160 Blackjacks, escorted by supporting airplanes, flew missions over the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the North Pole. The official Russian term for such flights is “combat patrol.”

Flights have continued sporadically ever since. The Canadian minister of defense said in 2014 that the Canadian air force was intercepting between 12 and 18 Russian bombers a year off the Arctic coast.

The organization for air defense has changed repeatedly. Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, US homeland defense was grouped under the unified Northern Command, whose commander also heads NORAD. Today, however, the focus is again on Russia.

Pacific Air Forces 11th Air Force, formerly Alaskan Air Command, provides interceptor forces in Alaska under NORAD control. Air defense of Iceland is by NATO squadrons, rotating in and out of Keflavik. Air Combat Command’s 1st Air Force, with 10 Air National Guard wings, performs air defense of the continental United States.

For whatever reason, there was a surge of Bear incursions in the spring of 2017. In April, Tu-95s approached the coast of Alaska four days in a row and were met by USAF F-22s and Canadian CF-18s. In May, two Tu-95M bombers were intercepted by F-15s off the Alaskan north slope. This time the Bears were not alone. They were accompanied by a pair of Su-35S Flankers, Russia’s best fighter aircraft.

In August 2017, Tu-95MS Bears and their Flanker escorts flew routes over the Pacific, the Sea of Japan, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea, generating scrambles by the Japanese and the South Koreans. Last year, F-15s, F-22s, and CF-18s began to practice and hone their identification and intercept procedures by flying against US B-2 and B-52 bombers.

“The point of this exercise is for the United States to take it [Russia] seriously as a strategic adversary,” Michael Koffman, an analyst at the Woodrow Wilson Center, explained in 2015. “Moscow’s objective is to change the perception of Russia, which is currently seen as a regional power in structural decline.”

Resumption of the combat patrols added to Putin’s political popularity at home, Koffman said. “Russia’s leaders want to be considered as the existential threat the USSR was, a country the United States negotiated and compromised with, instead of chiding, sanctioning, and ignoring.”

John T. Correll was the editor-in-chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributor. His most recent article, “Targeting the Lufftwaffe,” appeared in the March issue.