The moon's farside, which always faces away from the Earth, is shown in a photo taken by Chang’e 4's companion relay satellite. China National Space Administration? photo.

China wrote itself into space history Jan. 2 by landing a five-foot long robotic rover on the moon’s far side. It’s the first time a spacecraft has soft-landed on the far side, which always faces away from the Earth, where it will conduct a number of experiments from radio astronomy to botany. The Chang’e 4 mission is enabled by the use of a communications relay satellite in the lunar vicinity; another first?. Without it, there could be no direct communication with the lander, as radio transmissions would be blocked by the moon.

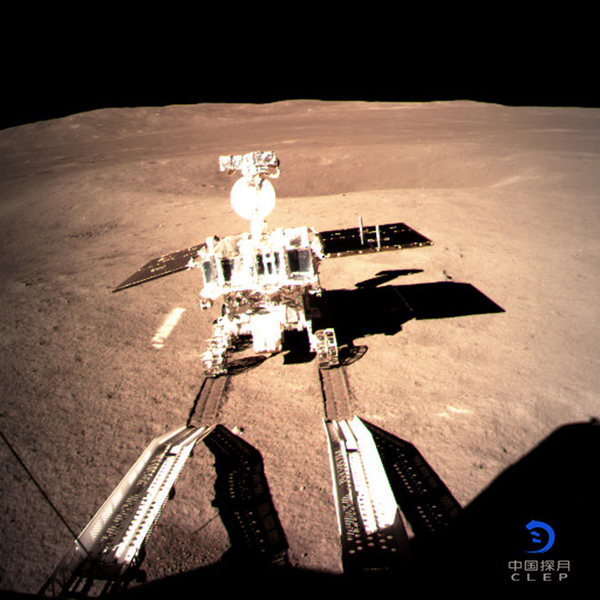

Yutu 2, Chang’e 4?’s lunar rover,? descends to the Moon’s surface on Jan. 3. Photo by the China National Space Administration?

Yutu 2, Chang’e 4?’s lunar rover,? descends to the Moon’s surface on Jan. 3. Photo by the China National Space Administration?

Given that only three years elapsed between the Surveyor probe’s June 1966 first soft-landing on the moon and the first steps there by US astronaut Neil Armstrong, is China poised to deposit people on the lunar soil in the next few years

The answer is, probably not, although China has delighted in springing technology surprises on the West in recent decades. The first space flight by a Chinese taikonaut in 2003 and the appearance of a Chinese stealth fighter in 2010—seven years ahead of Pentagon predictions—were among those technology curveballs that came with little warning.

The latest public version of China’s space exploration roadmap, which came out in 2018, calls for Chang’e 5, to be lofted on a Long March 5 heavy-lift rocket and fly autonomously to the moon, where it will collect samples and return them to the Earth later this year.

China’s attention will then shift first to an asteroid sample return mission about 2024, and Mars, where it plans orbiters and landers starting in the 2020 timeframe, leading up to a sample-return mission in 2028; around the same time as NASA’s own Martian sample return mission.

In the meantime—date not yet publicly set—China plans to land taikonauts on the moon, probably not later than 2028. Its space roadmap calls for an uninhabited lunar research station prototype around 2030, to be followed by a lunar base in the 2030s. These lunar bases would research energy supply solutions, “live off the land” use of lunar materials such as oxygen and water, self-erecting structures, lunar-based radio astronomy, and robotic exploration of the lunar surface. Also in 2030, China plans its first deep-space missions to the Jupiter system and investigation of Jupiter’s watery moon, Europa.

Among Chang’e 4’s experiments is a small greenhouse, which will test whether potatoes and a cabbage-like plant can grow on the moon.

Coincidence? Chang’e 4 landed in the crater Von Karman, named after the US Army Air Force’s first Scientific Advisor Board chairman, Theodore Von Karman, who also founded the US Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which has managed most American deep-space exploration missions. The crater is in the Aitken basin, an even larger south polar crater where liquid water may be deposited just below the lunar surface.